Forschung

Good Deeds or Good Deals?

The market share of sustainable alternatives often lags miles behind suppliers’ expectations. While lacking credibility of sustainability claims is frequently cited as a plausible cause, new experiments suggest that in actual transactions, consumers have only weak sustainability preferences to begin with.

In surveys, a large majority of consumers (often around 80%) report that they consider the environmental impact of their actions when making purchase decisions. While market data also suggests that there is a certain demand for sustainable products, there seems to be a striking gap between consumers’ market decisions and their survey responses. For instance, the German Environment Agency has recently published new data suggesting that in 2022, the weighted market shares of products with official ecolabels amounted to about 12%. While this figure represents more than a tripling of these products’ market share since 2012, it still falls far short from what might be expected from consumers’ reported sustainability preferences.

Social and scientific discourse and regulatory efforts (for instance, the recent European Green Claims Directive) seem to have identified the insufficient credibility of producers’ sustainability claims as the central reason for consumers’ apparent unwillingness to put their money where their mouth is. To be sure, greenwashing scandals and disappointing ecological performance of ostensibly sustainable alternatives appear to be the daily fare of the stricken environmentally concerned consumer. Thus, it would come as little surprise that consumers’ sustainability preferences do not manifest in sustainable consumption, simply due to a lack of credibly sustainable alternatives. Such a stance, however, begs a vital question: Can we be certain that consumers actually have strong sustainability preferences in the first place?

To address this question, several more must be posed. Do consumers even really prefer to buy sustainable products, and furthermore, are they also willing to pay a price premium for them? Or has the strength of consumers’ sustainability preferences generally been overestimated? Many previous studies have either relied on mere self-reports or on hypothetical and otherwise inconsequential decisions. Maybe participants in these studies just opted for sustainability because it is the socially desirable choice. In the marketplace, however, consumers might prioritize good deals over good deeds.

Investigating Sustainability Preferences in Real Transactions

To answer these questions, researchers at the Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions (NIM) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) constructed a rather abstract but consequential interaction formalizing the crucial features of a purchase decision in which the sellers can make a sustainability claim. Essentially, a seller demanded a price, and if a buyer indicated a willingness to pay higher than that price, the transaction was completed, and both parties received a payoff according to the price demanded by the seller. Like in real-life purchase decisions, higher prices increased sellers’ payoffs at the expense of the buyers’ payoffs and vice versa. If sellers and buyers could not agree on the price, the transaction was not completed, and no one received a payoff. Crucially, sellers could choose to donate a percentage of their payoff to an environmental charity. Through this choice, sellers could complement their offer with a sustainability claim, as a successful transaction would then not only benefit buyers and sellers but also the environment. Thus, the experiment showed whether sellers who make a sustainability claim demand higher prices to pass the costs associated with the claim to the buyers and, more centrally, whether buyers would be willing to pay the price premium for offers with a sustainability claim.

Generous Sellers and Reluctant Buyers

The sellers in the experiment frequently chose to make and implement sustainability claims and thereby sacrificed some of their profit. Interestingly, they did not demand a price premium and largely paid their donation out of their own pocket. Furthermore, if they had the opportunity not to implement their sustainability claim entirely, 75% were trustworthy and walked their talk (if they lied, a majority of course chose to overstate their actual efforts). Therefore, as sellers, people indeed seem to have measurable sustainability preferences.

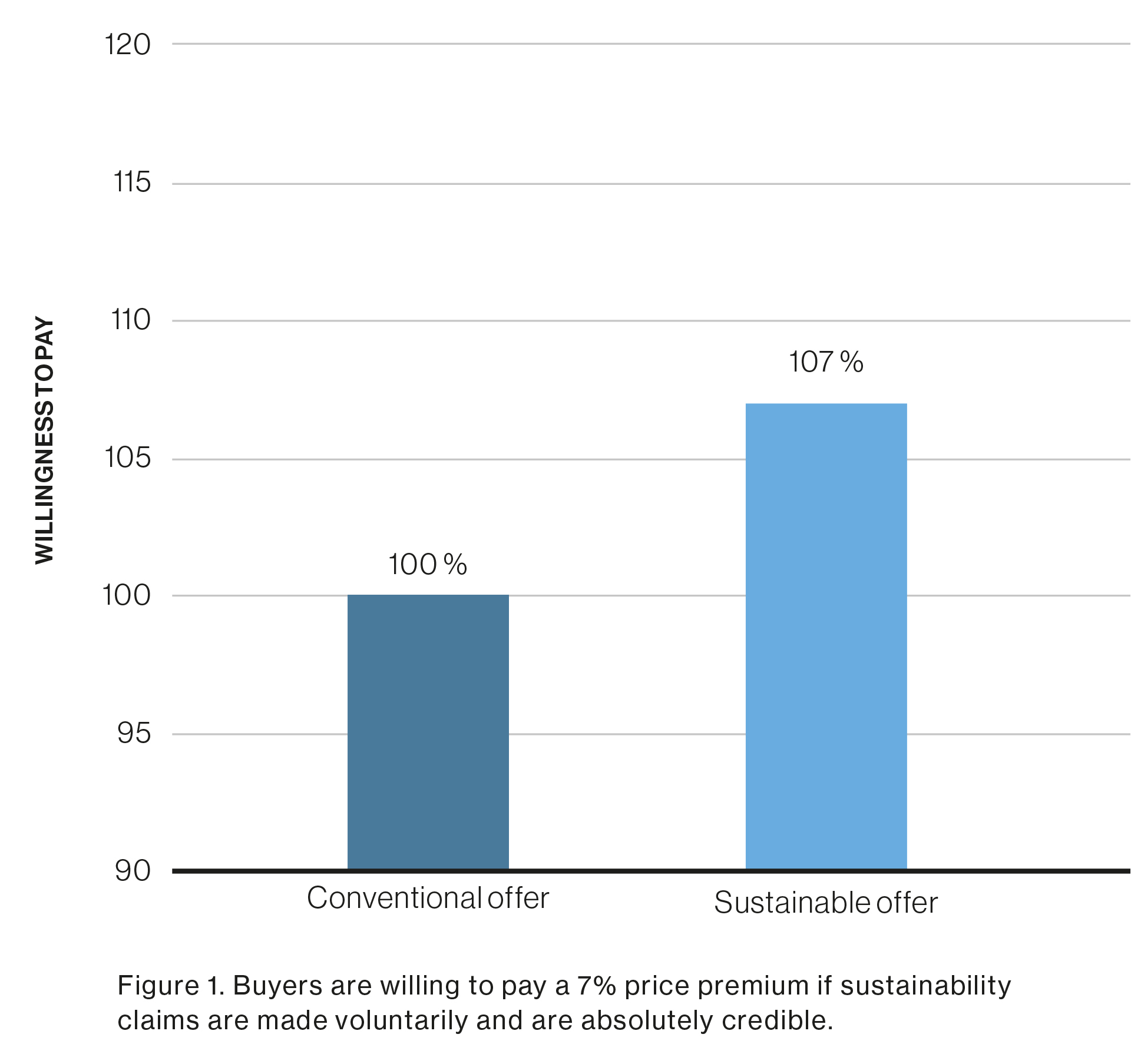

The picture is more disillusioning when looking at buyers’ decisions. Even if the sustainability claim was absolutely credible (i.e., if buyers knew how much a seller donated to the charity), there is only weak evidence suggesting that buyers were willing to pay a price premium. If there was any further uncertainty surrounding the sustainability claim, buyers did not show any willingness to pay more for sustainable offers. At the same time, buyers facing uncertainty seemed to expect that sellers would donate to the charity, as their willingness to pay was slightly higher irrespective of the information they had about the offer. By and large, it nonetheless seems that good deals are more important to buyers than good deeds.

Distrusted or Unappreciated? Sellers Must Get to the Bottom of Their Customers’ Attitude-Behavior Gap

In sum, the current evidence suggests that consumers might not have particularly strong sustainability preferences. Furthermore, doubts regarding the credibility or trustworthiness of a sustainability claim disperse any remaining willingness to pay a price premium for sustainable alternatives. The findings from this research project urge caution regarding the expected demand for sustainable alternatives. If businesses are uncertain about the strength of consumers’ sustainability preferences, evaluating the market potential of sustainable alternatives remains problematic. In any case, trustworthy communication of sustainability claims (e.g., via certified labels and regulation of admissible claims) remains paramount to activate the surprisingly subtle sustainability preferences consumers do seem to have.

From a more conceptual perspective, this project highlights that the infamous “attitude-behavior gap” in consumer decisions may be explained on several different levels. Sometimes, the gap may be knowledge driven—for instance, if attitude-related knowledge is not available during the decision or if attitude-relevant information about the choice options is lacking (e.g., because the environmental impact of a choice option is unknown). In other cases, the gap seems to be preference driven, such that attitudes are inherently biased (e.g., by social desirability) or insufficiently reflect trade-offs between different features of a decision (e.g., the trade-off between a good deed and a good deal). Finally, the gap may also be trust driven, as in the case of sustainability claims that are not credible or are perceived as greenwashing. Each case requires a very different approach to bridge the gap between attitudes and behavior, and a good theoretical understanding of a problem is therefore often a prerequisite to finding effective practical solutions.

KEY INSIGHTS

- Sellers demonstrate sustainability preferences and even accept profit reductions to implement sustainability claims.

Consumers do not exhibit strong sustainability preferences and are only willing to pay a premium if sustainability claims are voluntary and highly credible.

The consumer attitude-behavior gap can result from lack of information, biased preferences, or trust issues.

In order to develop effective practical solutions, it is crucial to identify the underlying theoretical problem keeping consumers from choosing sustainable products.

Projektteam

- Dr. Matthias Unfried, Head of Behavioral Science, NIM, matthias.unfried@nim.org

- Dr. Michael K. Zürn, Senior Researcher, NIM, michael.zuern@nim.org

Kooperationspartner

- Sebastian Goerg, TU München

- Martin Speckner, TU München

Kontakt