Forschung

Branding in the Circular Economy

PHOTO: SVITTL ANA KUCHINA , GETTY IMAGES

While introducing a circular economy could reduce the catastrophic environmental impact of the fashion industry, consumers remain hesitant to purchase recycled or reused items at scale. Branding is an established approach to subtly promote consumers’ trust. Unfortunately, recent experimental data suggests that branding is unable to close the trust gap afflicting circular fashion.

For decades, the fashion industry has been dominated by a linear take-make-waste approach, an approach that produces high quantities of low-quality products from primary materials. The apparent demand for several collections per year is mirrored by high-frequency production as well as the short-lived usage of clothes. This dynamic generates millions of tons of clothes per year that are produced, worn, and thrown away. Every second, the equivalent of a truckload of clothes is burned or buried in landfills. To produce such a vast amount of clothes, the fashion industry uses around 60% of the total global textile output, which includes numerous natural and nonrenewable resources. If fashion production continues unchanged, it is projected to account for a quarter of the world’s carbon emissions by 2050. Such numbers clearly demonstrate the fashion industry’s substantial contribution to global challenges such as resource scarcity, waste, and global warming.

In response to these challenges, the circular economy has emerged as a promising solution that can potentially reduce resource and energy consumption as well as waste. Many fashion brands, such as fast-fashion giant H&M and green-fashion brand Armedangels, have started launching circular products, including secondhand clothes, recycled garments, and refurbished apparel. However, circular fashion faces numerous barriers, such as consumers’ product perception and willingness to pay.

Despite growing environmental concerns and interest in sustainable fashion, previous studies have indicated that consumers are hesitant to accept circular products because they associate sustainable fashion with low functionality, high risks, and clothes contamination. Put simply, consumers appear to be skeptical about circular products and do not trust them to the same extent they trust linear products. The reason for these perceptions seems to be a lack of knowledge about product history, quality, environmental impact, and the remanufacturing process the product goes through. To address this challenge, researchers at the Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions (NIM) and the University of Nuremberg (FAU) conducted an experiment to investigate whether brands might be capable of closing this “trust gap.”

INFO-BOX

Linear business model: A linear business model is a traditional approach in which firms follow a straightforward value chain. Under this approach, products are produced from raw materials, are used, and then, at the end of their life, are thrown away.

Circular practices aim to create a closed-loop system in which resources are regenerated rather than thrown away. A circular business model promotes sustainability and reduces environmental impact.

Circular business model: A circular business model is an approach focused on maximizing resource efficiency and minimizing waste by keeping products and materials in use for as long as possible through reuse, refurbishment, and recycling.

- Reused (i.e., secondhand) products are an example of an approach to extending the life of products without any transformation.

- Refurbishing is a process where used products are collected, disassembled, cleaned, have parts repaired or replaced, and, in the end, are reassembled. In the case of clothing, the products may not carry their original identity or functionality. For instance, a pair of trousers can be refurbished into a coat or a skirt.

- Recycling is a process of decomposing textile waste into raw materials, including reprocessing procedures such as shredding fabric and pulling out fibers. From the resulting new raw materials, such as yarn and fabric, new clothing products are made.

Can Brands Bridge the Trust Gap Between Linear and Circular Products?

In general, consumers often use a brand to infer product attributes that are difficult to directly observe. Therefore, the image of a brand can increase consumers’ trust in its products. The experiment examined the effect of green-fashion brands and fast-fashion brands on items’ perceived sustainability and consumers’ quality perception and willingness to pay for circular clothes.

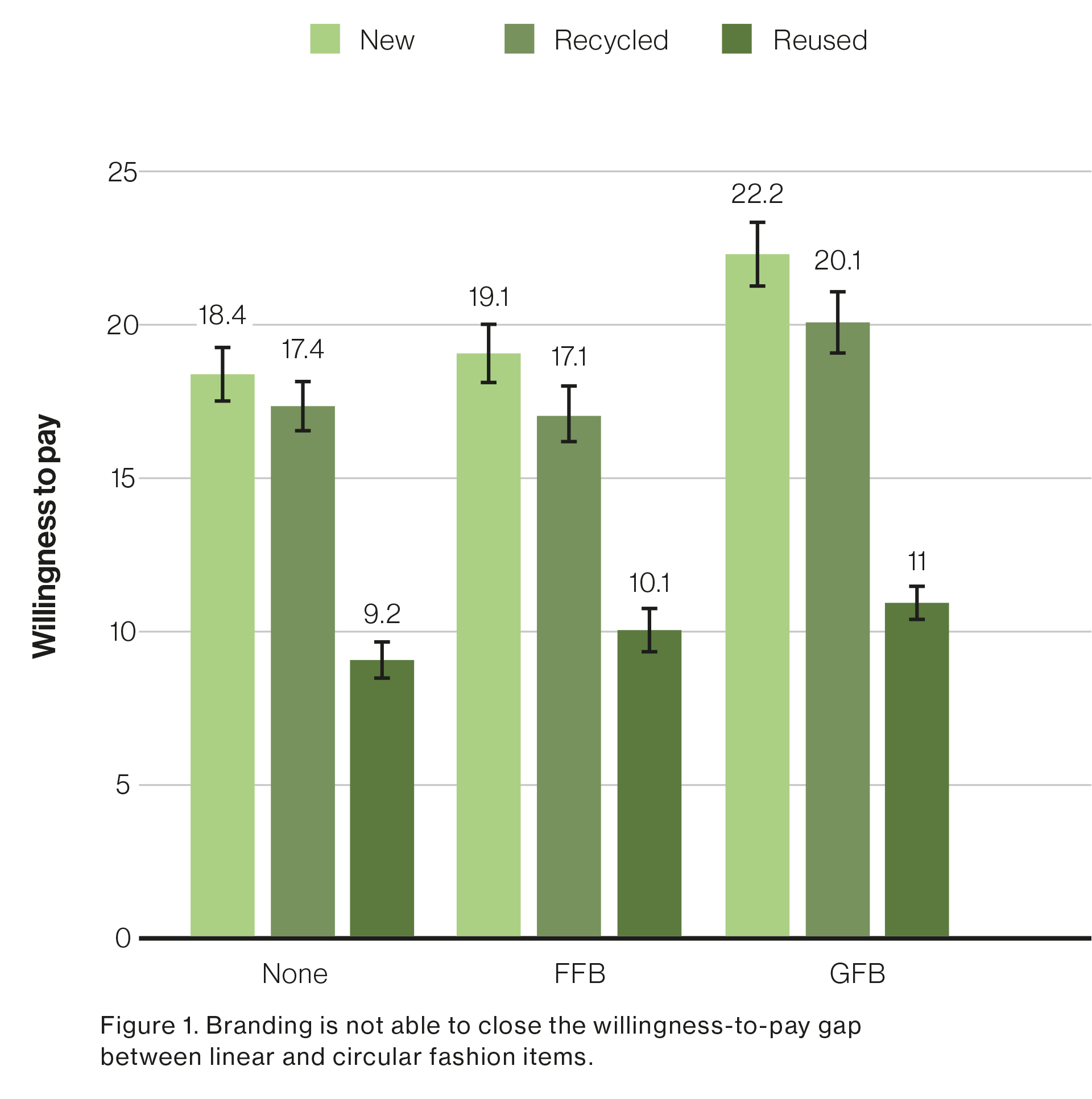

The fndings show that circular clothes differ considerably in terms of their perceived quality and consumers’ willingness to pay. The highest perceived quality and willingness to pay exists for new (i.e., linear) products, followed by recycled, refurbished, and, lastly, secondhand clothes. The remanufacturing process might explain the higher quality perception and willingness to pay for recycled and refurbished products compared to their secondhand counterparts, as remanufacturing reduces the variance in quality and can create associations with terms such as “inspection” and “quality control” in consumers’ minds.

Notably, brands seem to be unable to close the gap between new and circular clothes. Indeed, they even appear to expand the gap. For recycled clothes, both green-fashion and fast-fashion brands seem to increase the gap in perceived quality. Regarding refurbished products, both types of brands increase the gap in quality perception and even in willingness to pay. Therefore, nonbranded circular products exhibit a lower gap in perceived quality, while refurbished products exhibit a lower gap in both perceived quality and willingness to pay than branded circular products. This outcome could mean that brands may want to consider launching circular products under a new brand that is not connected to their initial branding. It should be noted, however, that, overall, perceived quality and willingness to pay are generally higher if products are associated with a green-fashion brand.

Consumers Misjudge the Environmental Impact of Circular Products

The findings suggest that secondhand clothes constitute a distinct category characterized by low perceived quality, surprisingly low sustainability, and low willingness to pay. Moreover, this outcome cannot be mitigated by brands. The gaps in quality and willingness to pay do not significantly differ between non-branded and fast-fashion branded products. Therefore, it seems that if goods enter the secondhand market, they have a similar level of perceived quality and economic value, and the brand no longer plays an important role.

Regarding perceived sustainability, the study shows that consumers do not perceive the sustainability of clothes according to their actual environmental impact. Recycled clothes require many resources and a large expenditure of energy in their reproduction yet are perceived to have higher sustainability than refurbished or reused clothes. Also, neither brand type decreases the perceived sustainability differences between circular and new products compared to non-branded products—that is, even green-fashion brands, which were assumed to overcome skepticism toward sustainability claims and increase perceived sustainability, do not diminish this perceived difference. This outcome could mean that the product line extension toward circular products does not fit a brand image and is perceived as unauthentic.

Brands Face Challenges in the Circular Economy

In summary, implementing a circular product line extension can be difficult for brands regardless of their image. If brands consider adding a circular product, the findings suggest that recycled products could be the best choice, as recycling is perceived as the most sustainable approach with the highest perceived quality and subsequently commands the highest willingness to pay among the various circular products.

For secondhand products, the results suggest that green-fashion and fast-fashion brands face similar challenges, with neither brand type yielding an advantage in terms of perceived sustainability. Also, while brands do not seem to increase the gaps in perceived quality and willingness to pay for secondhand products, they also fail to close it. In any case, pricing circular products remains problematic, and the findings suggest that a price premium cannot be imposed under any circumstances. However, costs may be lower for circular products than for new products, so companies need to carefully analyze their resource savings, redesign costs, and marginal returns to decide if implementing a circular line would be profitable.

KEY INSIGHTS

- Circular products are perceived to have lower quality than new products, and consumers show a lower willingness to pay for them.

- Circular products are ranked from better to worse as recycled, refurbished, and secondhand in terms of perceived quality and willingness to pay.

- Brands cannot close the gap in perceived quality and willingness to pay between new, linear clothes, and circular clothes. In some cases, brands even widen the gap.

- The perceived sustainability of circular clothes is contrary to their actual environmental impact.

- Pricing circular products is difficult and requires a careful analysis of costs.

Projektteam

- Dr. Michael K. Zürn, Senior Researcher, NIM, michael.zuern@nim.org

Kooperationspartner

- Antonia Kronmüller, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg

- Francisco Layrisse Villamizar, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg

Kontakt