Download

Download

Web3 and the Future of the Digital Platform Economy: The Tricky Business of Finding the “Just Right” Level of Decentralization

Digital platforms dominate our economy

Without a doubt, platform business models have revolutionized almost every industry, from e-commerce (Amazon) and operating systems (iOS and Android) to transportation (Uber), film (Netflix) and hospitality (Airbnb). In 2023, four out of the five most valuable companies worldwide operated based on platform business models. Often, these platform business models have made services more accessible and significantly reduced costs for their users. Platform business models enable the platform provider, as the intermediary, to make these improvements at low costs for their users as network effects lock in users and allow the provider to collect and monetize their data. This mechanism often leads to one strong player dominating the market, allowing them to monetize their monopoly-like position.

The recent upsurge in artificial intelligence (AI) has fostered fears that these platform businesses might become even more powerful. More than ever, critics are concerned that current regulations fail to mitigate these dynamics, as antitrust regulations have failed to prevent platform providers from acquiring even more market power. Regulators are often fighting an uphill battle as the platform businesses can often rely on much deeper pockets and smart lawyers who find new ways to play down their employers’ real power.

Decentralizing digital platforms comprises many trade-offs and careful consideration of the actual goals.

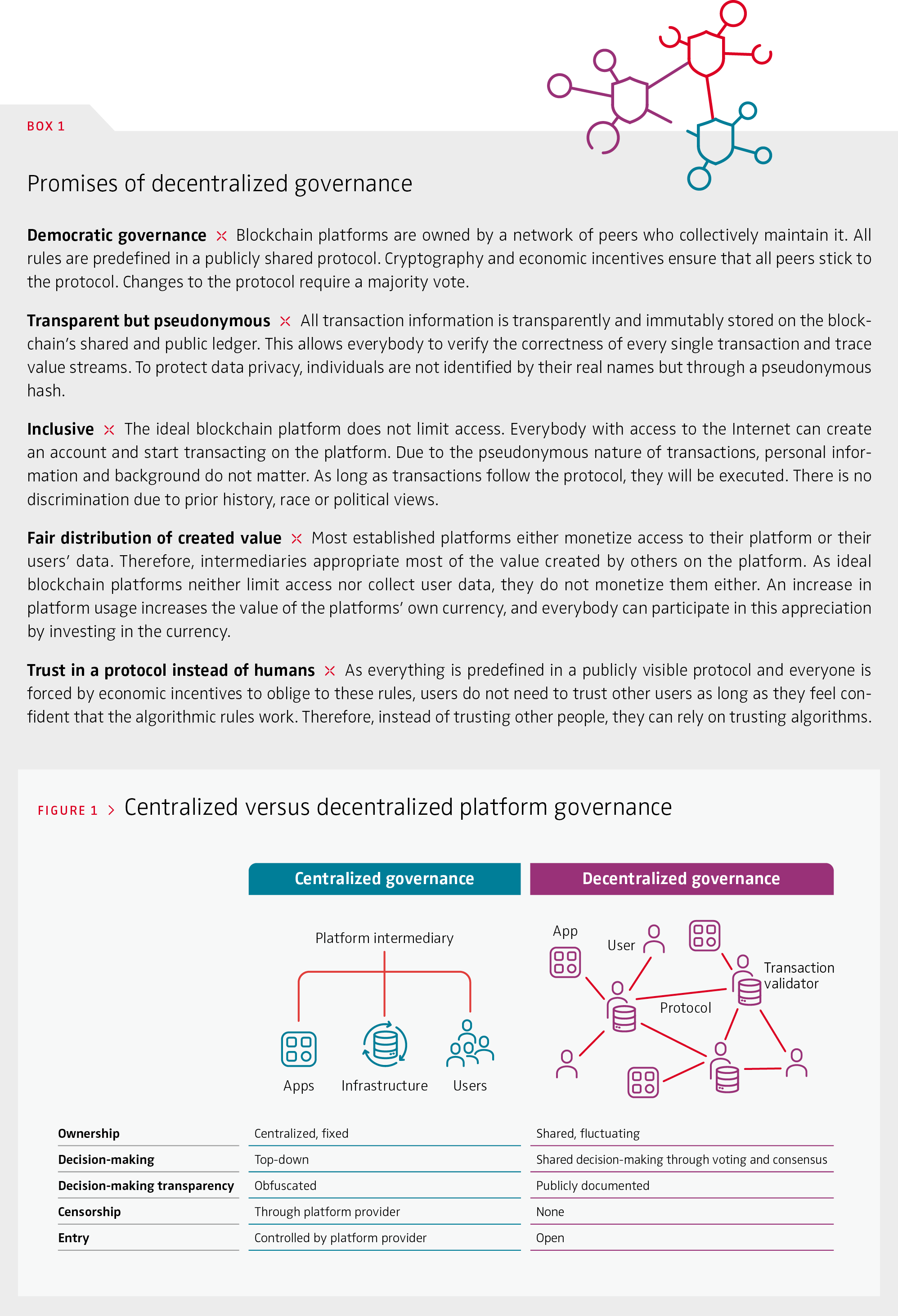

Promises of decentralized platforms

As an alternative to current regulatory efforts and to escape the dystopian fear of a few powerful platform companies controlling every detail of our lives, tech evangelists have praised blockchain technology and algorithm-based, decentralized governance as a potential remedy (see Figure 1). Their promise follows the same rhetoric: Blockchain technology allows the disintermediation of digital platforms and a fairer distribution of created value among those who contribute to it. This leads us into a new era of the Internet, often called Web3, that is more transparent, democratic and inclusive. These promises underlie a paradigm shift in how a digital platform is governed. Instead of one central party consolidating all decision authority and control over the platform, blockchain platforms rely on a predefined, algorithmically encoded and publicly visible protocol that enables a network of peers/ strangers to maintain the platform jointly. A clever combination of cryptography and economic incentives ensures that all parties adhere to the protocol, preventing any unilateral changes. Although blockchain protocols differ in detail, most permissionless blockchain platforms also implement additional desirable properties directly tied to decentralization, supposedly distinguishing them from their centralized counterparts (see Box 1 and Figure 1).

Decentralization is no panacea

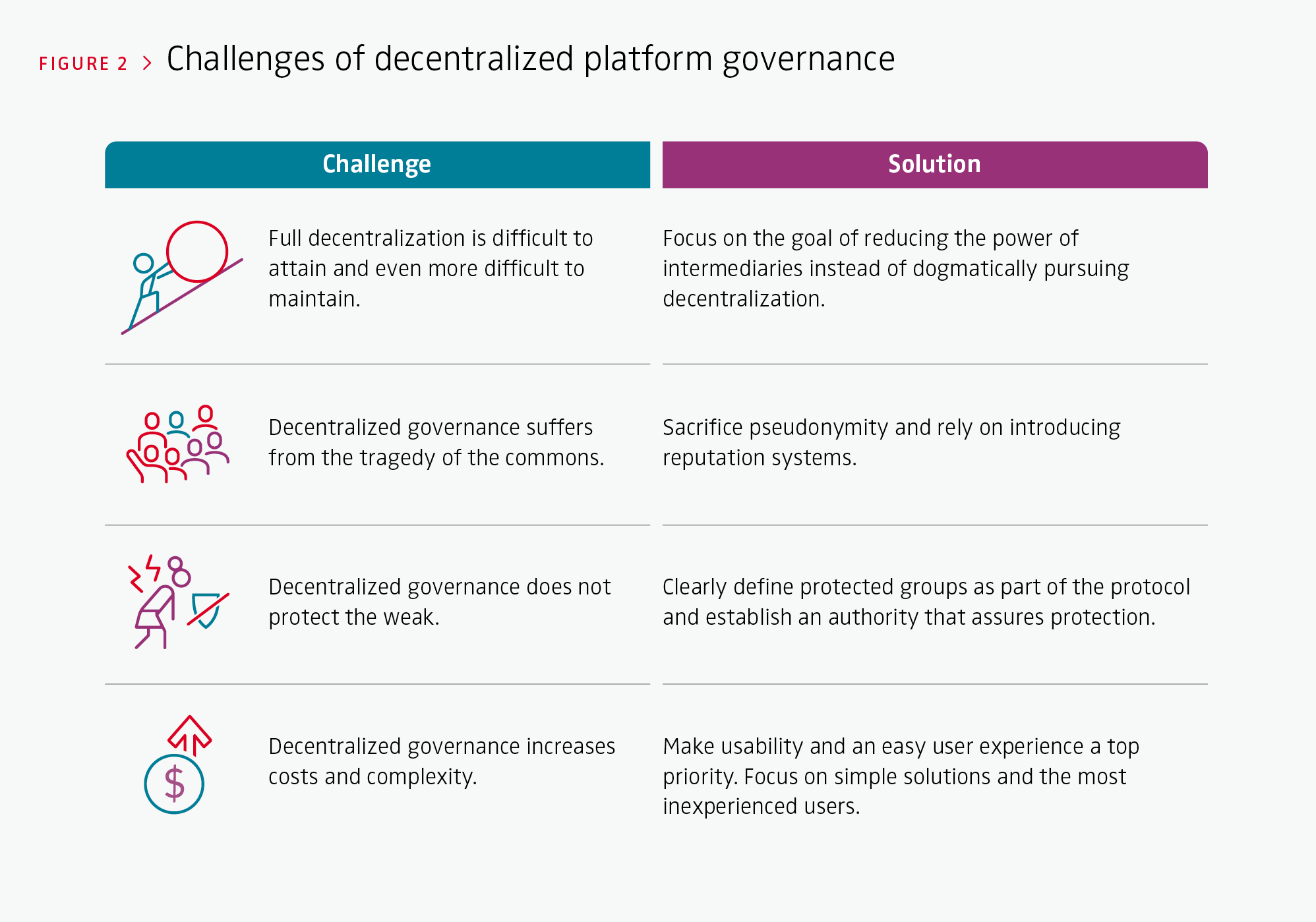

Despite the high hopes and theoretical potential of decentralizing digital platforms by devolving more decision power to their users through algorithms, decentralization is by no means a silver bullet. In fact, ample empirical research shows that decentralized platforms perform even worse than centralized platforms in terms of transparency, inclusion and democracy. Decentralized governance suffers from four inherent challenges (see Figure 2).

> Decentralization is challenging to attain and even more difficult to maintain

Complete decentralization requires that decision power is equally dispersed among all participants. In a blockchain-based system, this decision power is often implemented through governance tokens representing the stake one has in the system. These tokens are designed to appreciate in value with the platform’s growth and thus aim to incentivize their holders to vote for decisions that maximize the platform’s value. While this sounds like a desirable property at first glance, it becomes problematic when we acknowledge that holders differ in their time horizon, cost structures and how they can benefit from economies of scale. If enough myopic token holders are willing to sell their stake for a small profit to a holder benefiting more from a long-run perspective, the network will recentralize. Such dynamics are common in staking pools. For instance, Lido controls more than 30% of all staked tokens on Ethereum, or on Balancer, a popular finance application, one party accumulated enough voting power to tweak payouts in their favor. To tackle this issue of recentralization, digital platform providers can either resort to dedicated design decisions or regulations. For instance, they can design a governance token that is not tradable but instead omits a dividend based on the platform’s performance. However, this would require all parties holding such a token to be known, thus violating pseudonymity. Further, it would violate the principle of inclusion as it complicates becoming a platform member. Alternatively, the platform provider can create rules prohibiting a party from acquiring a particular share of the platform’s tokens. Again, this requires that the tokens’ actual holders are known. Further, it also requires a robust regulatory body with the power to enforce these rules, which can be seen as another form of centralized authority. Sometimes, some degree of centralization might be the best option to protect the promises of decentralized platforms.

Blockchain technology is expected to allow for the disintermediation of digital platforms and a fairer distribution of created value.

> Decentralization suffers from the tragedy of the commons

On decentralized platforms, nobody owns the platform. The platform is a shared good collectively maintained by a community of often pseudonymous users. To protect the platform from individuals engaging in opportunistic behavior, the platform’s protocol is usually set up to exclude this behavior by design or to punish it. However, to preclude opportunistic behavior, it has to be foreseen. While this might be feasible for simple transactions, it becomes more challenging as the platforms get more complex and draw more attention from opportunistic actors by increasing their market capitalization. Protecting these honeypots is challenging as entry is not restricted and protected by pseudonymity. Simultaneously, decentralized platforms are also less responsive to undesirable incidents as they have to form a consensus about possible actions before they can act. Reaching this consensus requires time and often suffers from freeriding problems because not everybody participates in voting and responding to such an incident. To tackle this issue, decentralized platforms could sacrifice pseudonymity, limit access to the platform through know-your-customer processes and install reputation systems that allow the identification of malicious actors. Although there is currently some experimentation with systems that would enable identifying a party without revealing its real identity, such proof-of-humanity projects are still in their infancy and require limiting access to a platform, thus confining openness and inclusion.

> Decentralization does not protect the weak

To ensure a decent level of decentralization, most decentralized platforms limit their capacity to allow users with less powerful machines to stay part of the network of peers maintaining the platform. To allocate this limited capacity, these platforms rely on a market mechanism that prioritizes traffic based on who is willing to pay the most. Although this seems like an efficient solution, it also means that people who cannot afford to pay these fees are excluded from the network. The vision of banking the unbanked becomes unreachable if a simple money transfer costs $10 in transaction fees, and only people who know how much money a transaction will make them will transact on such a platform. On Ethereum, decentralized finance applications crowd out transactions to non-finance applications, like games or social media applications, as they enable arbitrage through front-running. Front-running is a technique where more affluent users observe a planned transaction, copy it, pay higher fees and get it executed instead of the initial transaction. Techniques like this have turned decentralized platforms into a hostile environment where powerful entities that capitalize on weak and less experienced users have emerged. Therefore, decentralization has led to systematically exploiting the weak and foreclosing a fair distribution of created value. To tackle this problem, platform providers must acknowledge that some groups require protection and implement measures that prevent the weak from being weak. Again, giving up pseudonymity and introducing a reputation system might be a way forward. An alternative is to compromise decentralization on the network level and increase the capacity limit or prioritize transactions based on criteria other than the willingness to pay.

> Decentralization increases costs and complexity

Another challenge of decentralized platforms and governance is that they rely on redundancy and replication, which increases cost and complexity. While in a centralized system, information mainly runs to and from a central node, in a fully decentralized system, every node has to receive all information, store it and participate in every decision. Scaling such a system and making decisions are more complex and increase the costs of transacting, slowing decision-making. It also bears the risk that subsystems that develop their procedures and inhibit interoperability will emerge. While a centralized platform has high incentives to streamline information flows and make transactions across the whole platform as seamless as possible, decentralized platforms are again burdened by the tragedy of the commons. For this reason, centralized platforms are more successful in creating easy-to-use applications and exploiting network effects. Further, some decentralized platforms introduce new intermediaries to centralize tasks like enabling the transfer of funds across platforms.

Ways forward: Do not lose track of the initial goal

Using decentralization to push our digital economy into a new era of transparency, inclusion, democracy and fair value distribution remains a desirable vision. Today, however, we must acknowledge that complete decentralization is no panacea for reducing the power of intermediaries. Decentralizing digital platforms comprises many trade-offs and careful consideration of the actual goals. Pursuing decentralization for the sake of decentralization will not solve any problems. Although promising solutions that might fix the problems of decentralized governance are looming on the horizon, reintroducing some level of centralization might be a more reliable and available solution in the short run. The nature of intermediaries may change, but they are not likely to completely disappear. Even if the “ideal” vision of a fully decentralized and autonomous blockchain platform cannot be realized, this does not mean that blockchain technology has failed. It has created a sandbox for experimenting with different governance designs and mechanisms. The challenges of decentralization can be fixed by some degree of centralization or even with decentralized solutions, many of which are already being worked on by researchers. In the meantime, we should observe the blockchain space and pay attention to promising solutions to make the Internet a better place for everyone.

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Halaburda, H., & Obermeier, D. (2024). Decentralization vs. blockchain neutrality: The unequal burden of Ethereum’s market mechanism on dApps. SSRN. ssrn.com/abstract=4709286

Halaburda, H., Sarvary, M., & Haeringer, G. (2022). Economics of digital currencies and blockchain technologies. Springer International Publishing.

FURTHER READING

Bakos, Y., & Halaburda, H. (2022). Will blockchains disintermediate platforms? The problem of credible decentralization in DAOs. ssrn.com abstract=4221512

Bakos, Y., Halaburda, H., & Mueller-Bloch, C. (2021). When permissioned blockchains deliver more decentralization than permissionless. Communications of the ACM, 64(2), 20–22