Transforming Products into Platforms: Unearthing New Avenues for Business Innovation

Brands can benefit from adding platform elements to their existing products or services.

While the big platforms have become contested …

Platforms are one of the most powerful business models ever created. Network effects make them prone to exponential growth, almost infinite scalability and extremely strong defensibility. However, the success and the power of the platform giants have raised concerns and opposition. Critics question competitive and economic mechanisms, such as data monetization, privacy violations and manipulative and discriminatory algorithms. They request public and selfregulation as well as more balanced governance structures that take into account broader effects on society as a whole, as Annabelle Gawer (p. 30) and Daniel Sokol (p. 36) discuss in their articles.

… any brand can benefit from platformization

But platform models reach far beyond the giants, and one doesn’t need to become the next Amazon, Facebook, WeChat or YouTube in order to harness the power of network effects. Brands can use platforms to sell their products, but many brands can also benefit from adding some platform elements to their existing products or services. Every company in the world – from street vendors to car washes to manufacturers of physical goods and all the way to software vendors – can benefit from going through the exercise of brainstorming potential platform transformations of their products or services. This can and should be done in a playful and creative way. There are three key methods for doing so:

Method #1: Opening doors to third parties

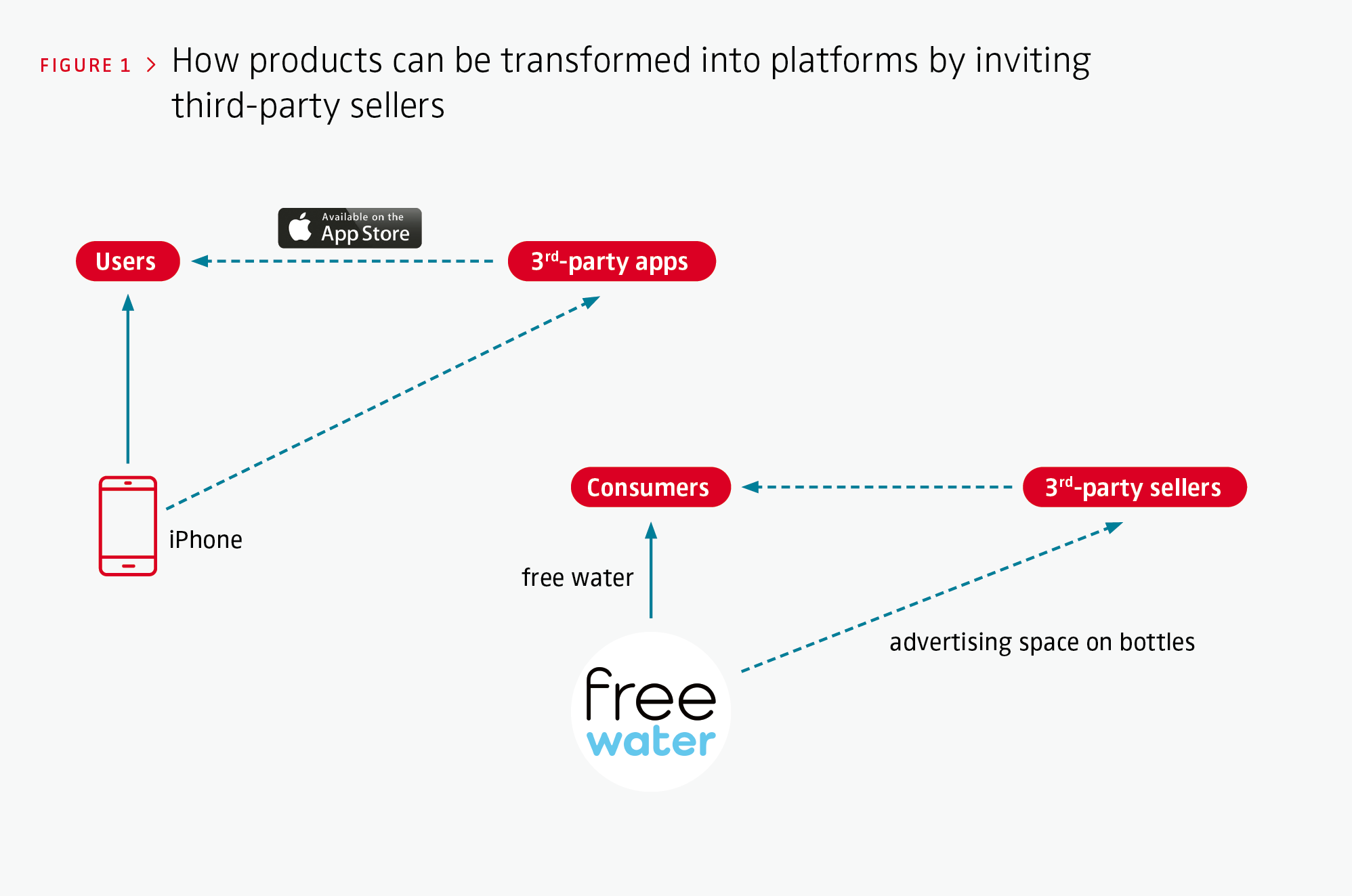

The idea of this method is to invite third-party sellers to promote or sell to your customers within your product or service. It is not about your product merely integrating with some existing third-party products. The end goal should be to have third parties build products and services that didn’t exist before and that are uniquely designed to work with your product. Figure 1 shows how this scheme works for two different brands.

> Allowing third parties to advertise on a product

A great example that was created in 2020 is FreeWater (see Figure 1). The company distributes natural spring water in aluminum bottles or paper cartons for free and sells advertising space on its bottles and cartons. FreeWater is admittedly an extreme example, in which the focal product – water – is provided for free. However, the potential for selling advertising space is clearly applicable to many products. Why couldn’t brands like Orangina, Poland Spring or Snickers also sell advertising space to third-party brands on their packaging? Of course, they would want to make sure that the third-party advertisers are aligned with, or complementary to, their brands. Presumably, a company would not want to allow competing brands to advertise on its products.

> Creating an app store around a product

While opening the door to third-party advertisers creates a new revenue stream, it does not really benefit the customers of the focal company’s products, except perhaps indirectly, in the form of lower prices. This is why the most powerful version of opening the door to third parties is something like creating an app store around your product, similar to what Apple did with its iPhone (see Figure 1). Indeed, opening up the iPhone APIs to third-party developers and launching the App Store in 2008 remains, to date, arguably the most successful and powerful implementation of opening the door to third parties. Since then, many other software companies have followed suit: Amazon opened up the AWS Marketplace in 2012, Shopify opened up the Shopify app store in 2009, Intuit launched the QuickBooks apps portal in 2014 and, most recently, OpenAI already has the GPT Store for ChatGPT. The initial iPhone apps didn’t exist before and were uniquely designed to work within the Apple world and the current GPTs are built around ChatGPT. Of course, over time, iPhone apps were ported to Android and other platforms, but it is still the case that developers first launch their apps on iOS and only later port them to Android. Similarly, GPTs did not exist before and are uniquely enabled by ChatGPT. And, in turn, they build an ecosystem of products and services around ChatGPT that OpenAI could not have dreamed of building on its own – just like Apple could never have imagined and built over 1.8 million iPhone apps. This is the true power of opening the door to third parties and unleashing innovations by third parties – it is no longer just a product, but a portal to many other functionalities and to an entire ecosystem, which makes the original product more valuable and more defensible. Let’s take the app store idea back to the first example we started with: FreeWater. For example, FreeWater could invite third parties to come up with new formulas of nutritious supplements that can be selected by consumers at the point of sale or online. While this may seem like a stretch from a business perspective, this thought experiment is meant to illustrate how creative and powerful the logic of opening the door to third parties can be.

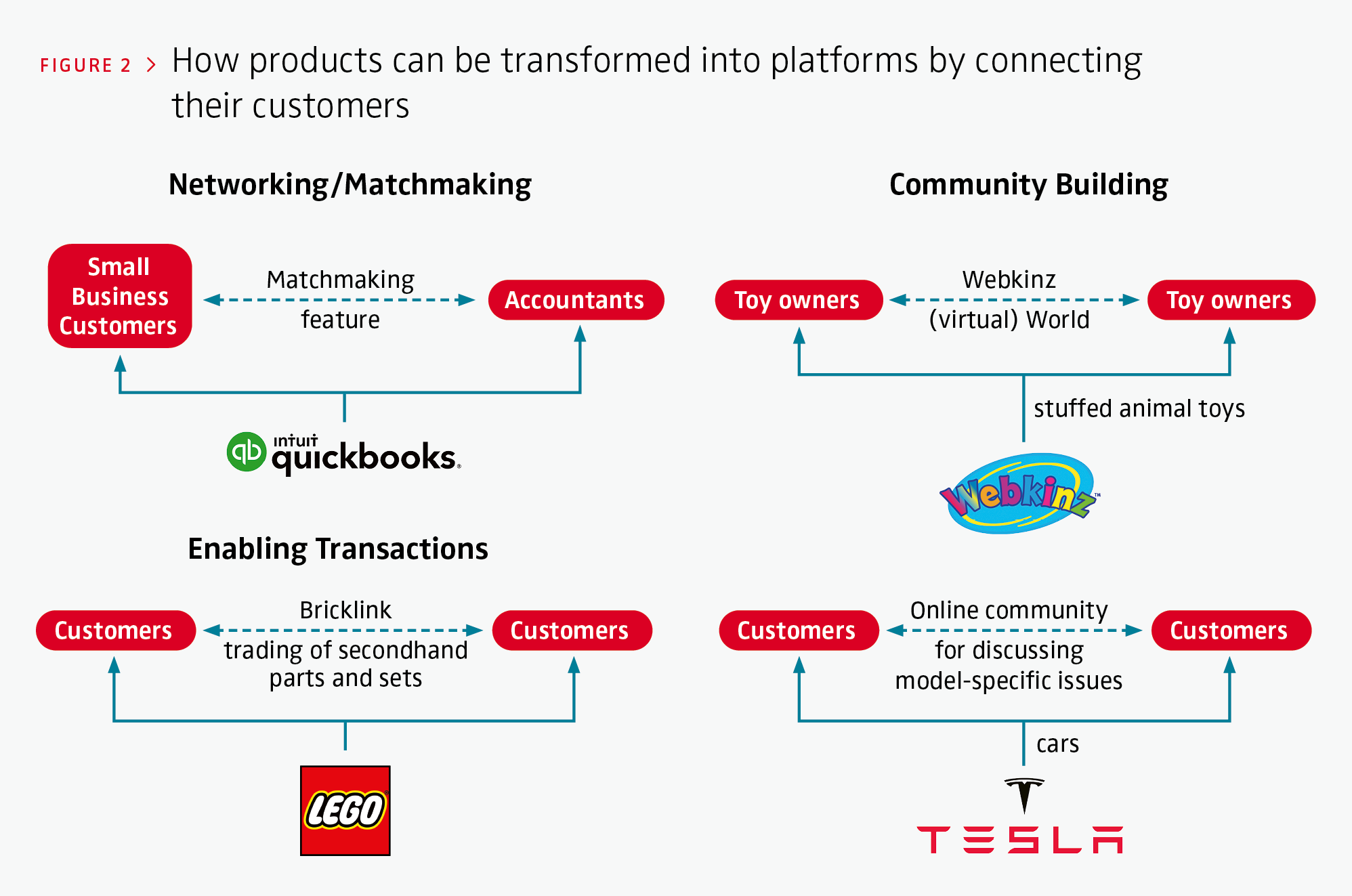

Method #2: Connecting customers

The idea with this method is to add to your product the ability to enable valuable interactions or transactions between your customers. It is about identifying useful ways in which your product can uniquely connect your customers and create value for them. There are different types of interactions that products can enable: business-related networking, social and even romantic matchmaking, exchange of information or experiences, or transactional. Figure 2 shows the basic scheme of this methods for four brands. We discuss these examples and others below.

> Enabling matchmaking

After the software company Intuit realized that many of the small business customers of its QuickBooks product were looking for accountants and that many independent accountants, who are also QuickBooks customers, were looking for clients, Intuit added a matchmaking function within QuickBooks that allows small businesses to find and contact accountants with relevant expertise in their geographic area – a business networking feature. Perhaps the two most memorable examples of products adding the ability to connect customers are Samsung’s Refrigerdating service and Virgin’s ill-fated in-flight flirting system. Launched sometime in late 2018–2019, Samsung’s Refrigerdating allowed consumers to match for dating purposes based on what’s in their refrigerators. A similar idea was implemented by Virgin America/Atlantic starting back in 2013: Virgin equipped its in-flight touchscreen system with the ability to send messages to passengers in other seats on the flight, as well as to order them drinks. This capability was later pivoted into an in-flight business networking system (apparently, several airlines offer some version of the latter today). The Virgin in-flight flirting capability predictably led to at least one instance of harassment, so the company eventually shut it down. While it is easy to poke fun at these two services, they do suggest an interesting opportunity: What products and services would benefit from enabling romantic or social connections between their users? Fridges and airline flights may not be obvious candidates, but books, movies, music and podcasts might be. For example, Kindle, Netflix and Spotify could incorporate a matchmaking feature into their services, based on content preferences. Discovering friends or romantic partners through shared book, movie or music interests would likely be appealing to many users and, in turn, would add new value to these services.

> Building communities

Many brands set up forums to enable their customers to communicate with each other. The goal is to allow customers to share knowledge and provide useful tips to each other so that they can get the best experience out of the products. Examples include Wolfram Mathematica’s vibrant user forum and Tesla’s online community for discussing issues regarding its various car models. A particularly creative example is the plush toy brand Ganz, which equipped each of its popular stuffed animal Webkinz toys with a playable online counterpart starting in 2005. The owner of each toy can activate a digital avatar via a secret code and then play with other toy owners in the virtual Webkinz World. The Webkinz virtual world concept may look like a marketing gimmick at first glance, but it is brilliant in at least two ways. First, it creates very real network effects around a common physical product: People no longer buy Webkinz just as stand-alone toys, but they also care about how many other people buy the toys and participate in the Webkinz virtual world. Second, the Webkinz virtual world, launched in 2005, was essentially a precursor to non-fungible tokens (NFTs) – unique digital assets that certify ownership and provide access to various features. Given the explosion of blockchain-based NFTs in recent years, many brands can emulate the Webkinz example by attaching NFTs to products such as shoes, clothes or furniture, and enable all sorts of interactive and social functionalities based on those NFTs to create communities around their products.

> Enabling transactions

In 2019, LEGO acquired BrickLink, a website that allows LEGO fans from around the world to trade LEGO sets, parts and mini-figures with one another. One could have worried that transactions on BrickLink might cannibalize sales of new LEGO sets, but this doesn’t seem to have been the case. It only strengthened the appeal of LEGO’s brand to its customers, giving them an opportunity to engage even more often with it.

In all of these examples, it is quite clear how enabling interactions or transactions among customers adds more value to the initial product.

Method #3: Reaching out to customers’ customers

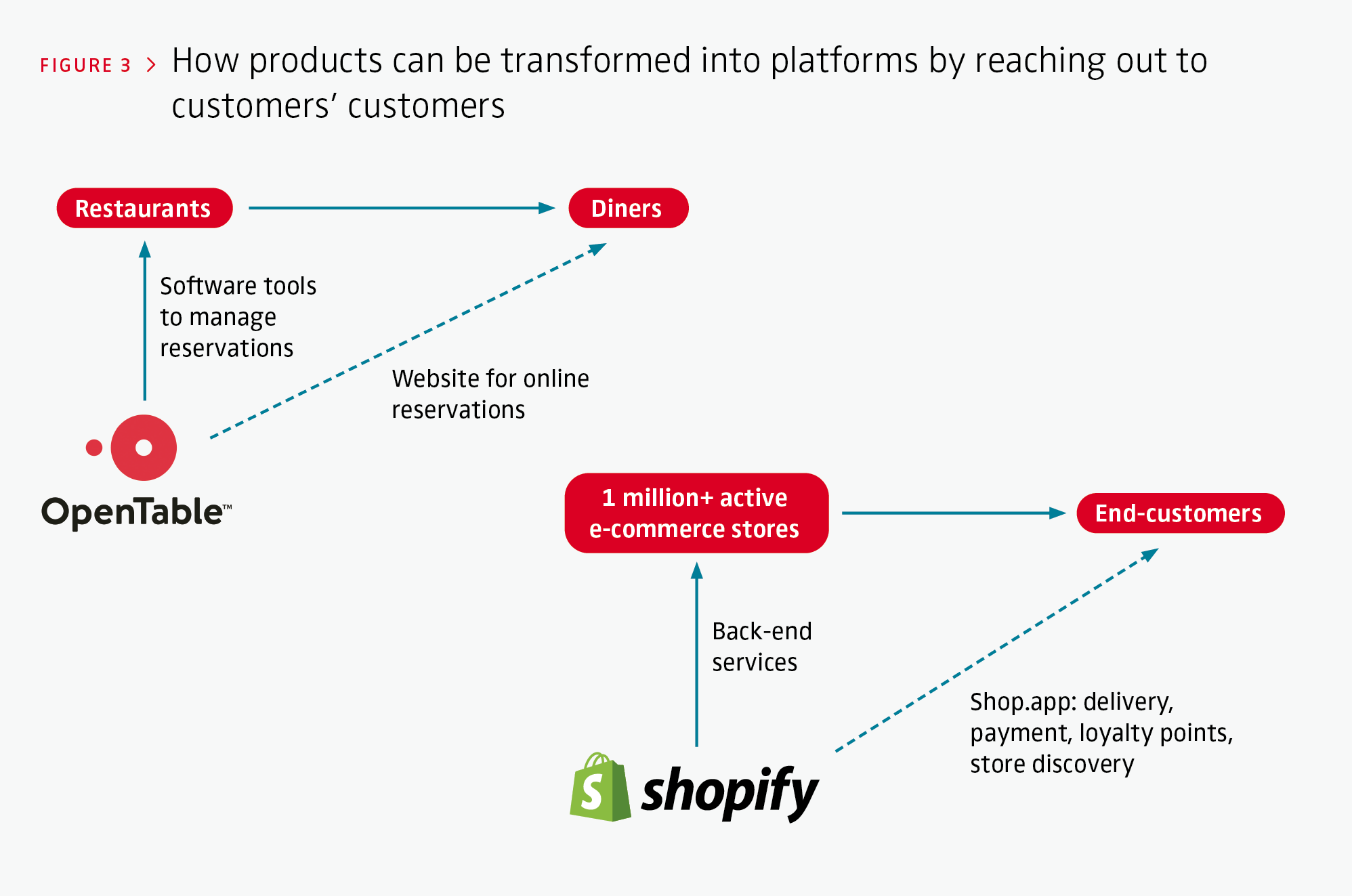

Our third method is relevant to B2B products or services, including ingredient brands (see Box 1). The idea is to reach out to your customers’ customers and offer them products or services that enhance their interactions with your own customers. The effort might be viewed with suspicion by your customers, who might fear that you are trying to wrest control over their customer relationship from them and eventually commoditize them. This is why it is very important that companies implement method #3 in a way that benefits not just their customers’ customers but also their original customers. Figure 3 shows two examples, which are further described below.

> Offering a complementary service

A classic example of successfully executing this method is OpenTable, which started off in 1998 as a supplier of software tools and point-of-sale systems to restaurants (its customers). Among other things, these tools helped restaurants manage their reservations with their own customers. After OpenTable had built a sizable customer base (of restaurants), it launched the reservation website to consumers (its customers’ customers), where consumers could discover and book tables at any of the restaurants that were using OpenTable’s software product. The reservation website transformed OpenTable from only a product supplier to restaurants into a two-sided platform (marketplace) with strong network effects.

> Improving end-customer experiences with the customer’s service

A more recent example is Shopify, the leading provider of e-commerce tools to its over one million online merchant customers. In April 2020, Shopify launched Shop.app, an application that improves consumers’ online shopping experience at Shopify merchants. The app remembers the consumers’ delivery and payment details to make it faster to complete forms at Shopify-powered online stores, creates a record of all their transactions, offers loyalty points when using Shop.app at checkout, provides a way to bookmark consumers’ favorite brands and has a “shop local” feature where users can browse nearby stores. While Shop.app has clearly transformed Shopify into a platform, it is interesting that the company has stopped short of creating a full-fledged marketplace like Amazon. com. The main reason is that it does not want its customers (the online merchants) to feel like they are being commoditized in the same way they are on Amazon’s marketplace. In the words of its CEO: “Amazon is trying to build an empire, and Shopify is trying to arm the rebels.” The Shopify example illustrates the fundamental tension inherent in building a platform by reaching out to your customers’ customers. In the case of Shopify, it is clear why Shop.app is appealing to end-customers, but the merchants (Shopify’s customers) also benefit: The checkout process is faster and more convenient for their customers, which means higher conversion rates and more repeat purchases.

Brands that build platforms around their products can’t go on cruise control

A word of caution is in order. When embarking on a product-to-platform transformation, a company goes from having full control over the entire product experience to a world in which third parties are interacting with one another on its product in ways not fully controlled by the company. The upside is that the original product owner benefits from value created by third parties without incurring the cost of producing that value. The downside is that the original product owner may ultimately be held liable by its customers for any issues created by the third parties. This issue arises with all three methods. A bad experience with a third-party GPT found in the ChatGPT store will negatively impact the ChatGPT brand. An abusive interaction between Webkinz World users will negatively impact Ganz’s Webkinz brand. And the moment Gore-Tex opens a marketplace connecting its brand customers to their customers, it will be at least partly held responsible for issues with its customers’ products. Therefore, brands should carefully screen third parties and put clear governance rules in place to make sure the platforms function as intended and deliver a positive experience to the customers of the original product.

Network effects are one of the strongest sources of power and defensibility ever invented.

No way around the platform economy

Today, it is impossible for brands to ignore digital platform opportunities. Network effects are one of the strongest sources of power and defensibility ever invented. They underlie some of the most valuable businesses in the world, from Amazon, Google, Meta and Microsoft in the United States to Pinduoduo and Tencent in China. In his article, Michael Zhang (p. 24) discusses the commonalities and differences between US vs. Chinese platform businesses. There are three ways for managers and entrepreneurs to leverage the power of platforms: build platforms around their brands, distribute their brands on existing platforms or build their own platforms. In this article, we discussed the many opportunities for brands that build platforms around their brands. In their article, Hemant Bhargava and his coauthors (p. 18) present a strategic framework for brands that use platforms like Amazon to sell their products. Brand commoditization is a threat, but it can be avoided, and brand identity can be shielded with the right measures. And finally, in terms of opportunities to build new platforms, there are still plenty of valuable Airbnbs to be built. In our interview (p. 52), Julie Roth Novack describes PartySlate, a platform she founded that connects businesses in the event management industry with people planning major events. While consumers find inspiration and their dream team to organize their event, planners, venues, entertainers, etc., get professional marketing support to grow their businesses and build their brands. Further, platforms can follow principles other than profit maximization or data monetization for the platform provider or middlemen. Hanna Halaburda and her coauthor (p. 40) analyze how blockchain technology could be used to make platforms more transparent, democratic and inclusive. Giana Eckhardt and her coauthors investigate platform models that focus on social value rather than scale and present alternative platform governance approaches, such as platform cooperatives (p. 46). Only if they are thoughtfully implemented and carefully monitored will any platform strategy create self-reinforcing feedback loops, sparking growth and keeping competitors at bay. If you are asking yourself whether the platform approaches should play a role in your business ventures, the answer is an unambiguous yes!

FURTHER READING

Hagiu, A., & Wright, J. (2024). Will that marketplace succeed? Harvard Business Review, 102(4), 94–103.

Hagiu, A., & Wright, J. (2021). Don’t let platforms commoditize your business. Harvard Business Review, 99(3), 108–114.

Altman, E., & Hagiu, A. (2017). Finding the platform in your product. Harvard Business Review. hbr. org/2017/07/finding-the-platform-in-your-product