Big Tech Platforms: What Are the Limits to “Big Brother” Surveillance and Influence?

Big Tech platforms are more influential than nations

Digital platform companies have become the poster children of the digital economy and can be found among the most valuable companies in the world. Big Tech platforms and their ecosytems have reached unprecedented levels of economic power. The combined market capitalization of just four companies – Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple and Facebook – stands at nearly $7 trillion as of March 2024, an amount close to the total market capitalization of the entire Euronext stock exchange and about a quarter of the value of the whole Standard & Poor’s 100 index of US stocks. The Big Tech platforms – Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Facebook – have become so large that they are wealthier and more influential than many countries. Google and Facebook dominate close to 60% of digital advertising. Google controls about 90% of Internet search in most markets (except China) and about 70% of smartphone operating systems with the free Android OS. In 2022, Amazon accounted for almost 40% of e-commerce in the United States and dominates e-books. Facebook is still the dominant social media and accounts for about 60% of social media activity.

As public regulation cannot cover all critical aspects or be ahead of developments, self-regulation is necessary to prevent exploitation.

Extensive platform power has raised concerns

It is no wonder that these platforms and their concentration of power have raised concerns. For the past few years, Big Tech platforms have experienced increasing backlash, and criticisms go far beyond anti-competitive behavior. Rather, they cut to the core of societal values and fear for fundamental human rights and democracy. One reason is that online platforms take vast advantage of the behavioral habits of billions of users. This data becomes a key resource that platforms leverage to enhance digital services, to develop new services and to enter new markets. In the context of ongoing and excessive data generation, capture and use, the following strategies or outcomes are under high scrutiny:

> “Free” services in exchange for data

Influential critics like Internet pioneer Jaron Lanier and former Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff have coined the term “surveillance capitalism” for the logic of “datafication” of human activities. They claim that it profoundly and negatively affects humans and society. Humans engage continuously and often unwittingly with organizations, and digital platforms in particular, which appear to offer them “free” services. Consider, for example, digital platforms’ ever-increasing capture and analysis of health data that allows its users to monitor themselves. The ever-increasing collection and analysis of quantified data about health can have severe negative effects, making individuals’ health legible to a broad array of actors outside recognized medical and clinical settings and giving them increased ability to know about, and engage with, people’s health. Users are enrolled into pursuing the platforms’ own profit goals, as the captured data allows platforms to manipulate users’ behaviors for their own benefit. These economic mechanisms can threaten core values of liberal societies, such as freedom of choice and privacy.

> Monetization of user-generated data via advertising

Digital platforms whose business models are advertising based capture and monetize user-generated data in ways that can generate huge profits, while end-users are not always aware of the role they play and receive nothing or little in return. They are “instrumentalized,” as their behaviors serve as an input in a business logic fueled by strategies of data-extractive businesses. Everyone who is on social media is getting individualized, continuously adjusted stimuli, without a break, so long as they use their smartphones. Lanier warns that what was once called advertising has transformed into continuous behavior modification. He argues that “what has become normal – pervasive surveillance and constant, subtle manipulation – is unethical, cruel, dangerous and inhumane.” He observes addictive mechanisms on social media platforms and assesses that they threaten free will.

> Data leaks and data transfers

The privacy of consumers on digital platforms is pervasively violated by digital platforms. For example, Facebook’s eagerness to get third-party apps connected to its network has led to mass data leaks, exposing sensitive information from hundreds of millions of people, as in the so-called Cambridge Analytica scandal. Facebook also eventually merged the infrastructures of Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and Instagram, after having promised years prior that it would not. This raises privacy questions around how users’ data may be shared between services. WhatsApp historically required only a phone number when new users signed up. By contrast, Facebook and Facebook Messenger ask users to provide their true identities. Matching Facebook and Instagram users to their WhatsApp handles could harm those who prefer to keep their use of each app separate.

For the past few years, Big Tech platforms have experienced increasing backlash, and criticisms go far beyond anti-competitive behavior.

> Pressure to disclose private information

Digital platforms also use so-called “dark patterns,” which are user interfaces that make it difficult for users to express their actual preferences or manipulate users into taking actions that do not comport with their preferences or expectations. Examples of dark patterns abound in privacy and security. For example, Google Maps repeatedly asks users whether a site they regularly return to should be labeled “home” or “work.” If the user agrees to label the geolocation, then the pop-up queries will cease. If the user clicks on “Not Now,” there will be more queries a few days later. The result is that the application may be so persistent in asking users to confirm personal information that they will eventually relent to prevent further nagging, not because they want to share this information. Platforms, for instance, sometimes design technologies and user interfaces that leave users with no choice, restrict their choice or provide them with insufficient or deliberately biased information, preventing them from making informed choices.

> Algorithms with true or false inferences about users

Privacy risks go beyond just the immediately collected data and extend to an even broader range of inferred pieces of data about individuals. Platforms can use big data, algorithms, predictive analytics, models and machine learning, exploiting raw collected data to create more and more inferences about individuals. In one of the more infamous examples of these techniques, an angry father confronted the retail store Target, demanding to know why they had been sending his teenage daughter coupons for pregnancy-related items. It turned out that Target’s systems had been able to (correctly) infer from the daughter’s online activities that she was pregnant – a fact the father had been in the dark about. Such examples have only proliferated in the years since that story emerged, demonstrating the importance of considering privacy when it comes to inferred data. These inferences are in turn used to manipulate, assess, predict and nudge individuals – often without their awareness and nearly always without any oversight or accountability. Moreover, these sorts of systems are often plagued by biases and inaccuracies.

Remedies against overexploitation of Big Tech platforms

The danger of digital platforms is that as they become dominant, they lose sight of what made them earn their position of centrality in the first place: acting as foundations of innovation or central actors that facilitate exchange across sides. With increasing influence, platforms often find it very hard to resist the temptation to become bottlenecks and overexploit their position. This, however, threatens the sustainability of the ecosystem in the long run and triggers resistance and criticism. This, in turn, can entail regulatory actions, either externally in the form of laws or internally by more balanced platform governance rules, or both.

Users’ sovereignty to make their own decisions needs special attention and should therefore be included in platform regulation.

> Public regulation

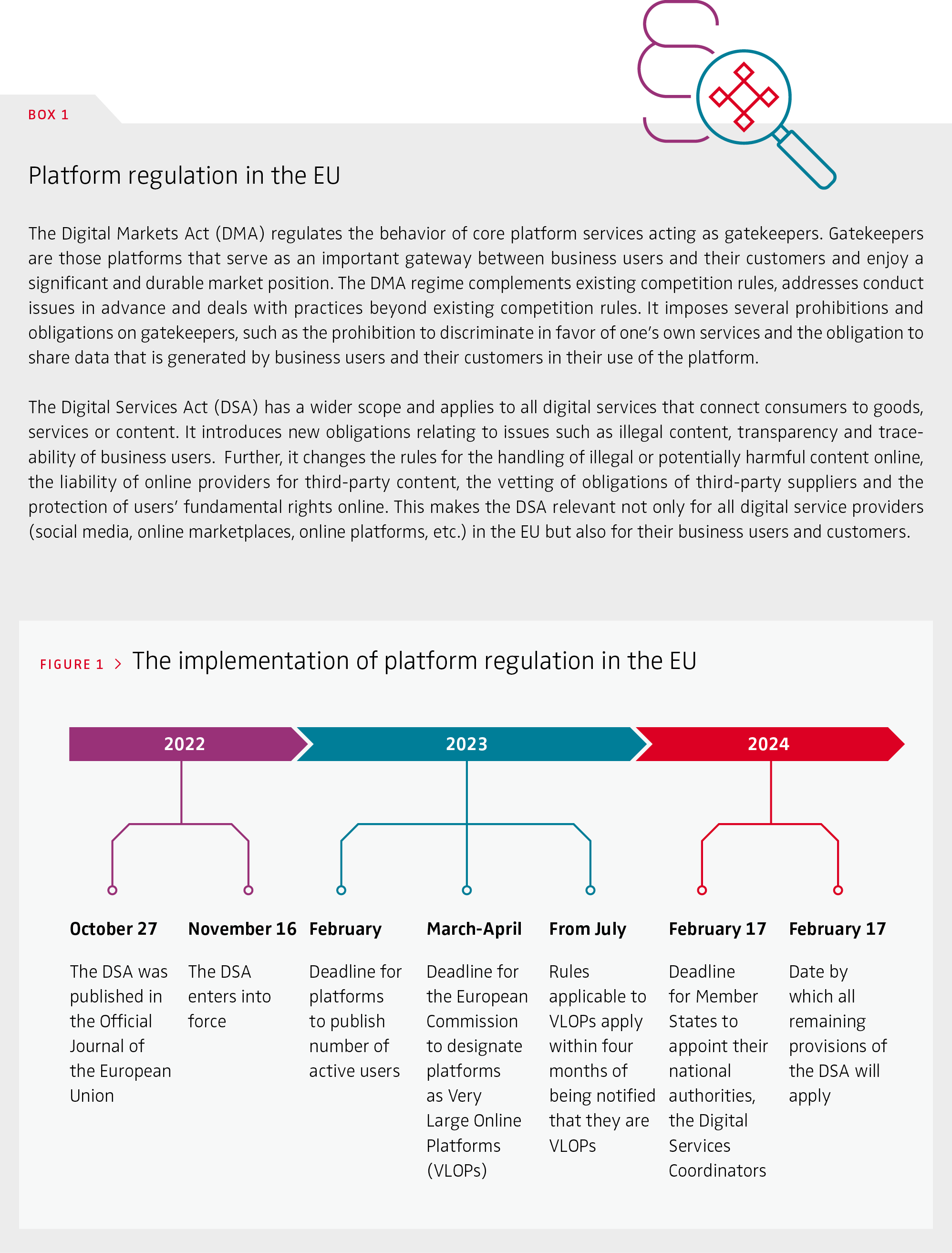

Several influential reports in Europe, Australia and the USA have contributed to informing regulatory agencies on these issues and methods of abuse of power, and the regulatory landscape has shifted. Proposals suggest, for instance, that platformdesigned user interface technologies and services should not aim to manipulate users into restricting their choices, mislead them or elicit addictive behavior. While most applicable policies and regulations were not designed explicitly for online platforms, the EU introduced specific platform-to-business regulation, which specifically aims to promote a better trading environment for online platforms’ business users, resolve problems associated with unfair practices between online platforms and their business users, and promote transparency in these business relationships. The Digital Markets Act (DMA) and the Digital Services Act (DSA) are both by now entirely applicable throughout the whole EU. Box 1 gives a brief overview of the scope and nature of these key pieces of platform regulation, and Figure 1 shows how it was implemented.

> Self-regulation and platform governance

As public regulation is only gradually and locally being implemented and cannot possibly cover all critical aspects or be ahead of developments, self-regulation is also necessary to prevent exploitation. Therefore, digital platforms also have to act as private regulators of their own ecosystems. They establish the rules through which their various users – individuals as well as organizations – interact and decide what behaviors to encourage or discourage and how to enforce them. Good platform governance is a balancing act between creating value for multiple sides of the platforms when these may have divergent incentives. The governance of platform ecosystems is not limited to hard rule-setting. It also consists of sending credible commitments to ecosystem members so that they continue to be affiliated with the platform. How platforms will govern their ecosystem of stakeholders will be structured by their design decisions on their digital interfaces. To reduce the societal backlash that Big Tech platforms are currently undergoing, these platforms need to address issues of data capture and data use and assess the way they present choice options and use data in manipulative ways.

Digital platforms’ roles and responsibilities are crucially important. Users should not be reduced to sources of data and deliberately manipulated by platform providers to prevent them from making legitimate decisions or making decisions contrary to their interests. In the digital world, users’ sovereignty to make their own decisions needs special attention and should therefore be included in platform regulation.

FURTHER READING

Gawer, A. (2021). Digital platforms and ecosystems: Remarks on the dominant organizational forms of the digital age. Innovation, 24(1), 110–124. doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2021.1965888

Lanier, J. (2018). Ten arguments for deleting your social media accounts right now. Henry Holt and Co.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books.